For Mike - Happy Birthday

There is a three-thousand pound egg set along Main Street in Mentone, Indiana, which is where I lived until I was eighteen. The egg was constructed in 1946 of concrete on a framework of steel. It’s purpose was to advertise the annual Mentone Egg Show -- a parade, a fish fry at the Fire Department, even an Egg Queen -- and the monster egg spent its first couple weeks of life on the Courthouse Square in Warsaw, the county seat, before it was plopped down on a vacant lot along Main Street in Mentone.

My older brother Gerald remembers looking into the oversized garage door opening where the men were working on the egg. “They were plastered as they plastered,” he said. He even named names.

Mentone’s egg has over the years been called the World’s Largest Egg. There’s competition however. Let’s demolish the competition as best we can. At least until we reach Portugal.

***

There is a large egg in Winlock, Washington. On its pedestal is written “World’s Largest Egg, Winlock.” Winlock’s original egg was made of canvas, but was eventually upgraded to fiberglass. It weighs just twelve hundred pounds. The folks of Winlock should travel to Mentone, see our much heavier egg, and paint over their boast. Or they could put “One of the ...” in front of “World’s Largest Egg” and make that egg plural. Further, on occasion, the Winlock egg is sometimes theme-painted, so that on, say, a Fourth of July, it may be painted in red, white, and blue, so as to resemble our country’s flag. Any hen that I’ve ever met -- and I’ve met a good many, for Mentone is “the egg basket of the midwest,” and I spent a lot of time odd-jobbing in chicken houses -- yes, any hen would fly from her nest in horror upon seeing any such monstrosity beneath her, and wonder what the hell sort of rooster she’d been fertlized by to deserve that.

So, c’mon, Winlock, get serious! Get out your paint.

A town called Vegreville in Alberta, has a nearly 26 foot long and 18 foot wide egg. They claim it to be the World’s Largest Egg. It is constructed of aluminum. In Alberta’s occasional 100 mph prairie winds their egg spins like a weather vane. It is anodized in gold, bronze, and silver, and is meant to resemble the particular fashion of Ukrainian Easter eggs called pysankas. I guess there must be a lot of Ukrainians settled in Vegreville.

Okay, it’s 5000 pounds. It’s over 25 feet long and over 18 feet wide.

It is said that over 12,000 man hours went into the design and fabrication of Vegreville’s egg. But could they have done it while drunk?

And it spins in the wind? No self-respecting egg should spin until it is introduced to a whisk or a blender. Okay?

Case dismissed.

The Guinness Book of World Records gives the nod to the town of Alcochete in Portugal. I have to hand it to those Alcochetians; their egg is 48 feet long and 27 feet in diameter. But they, like those Ukranians in Vegreville, call it an Easter egg.

When, by the way, and why, did eggs get mixed into the celebration of the Resurrection? What do they have to do with a man who, a couple of millenia ago, stepped from his tomb and ascended into heaven where he “sitteth at the right hand of God ... to judge the living and the dead”?

I prefer a secular egg.

Still, Mentone’s egg’s reputation is up against the Guiness Book of World Records. Couldn’t they add a category? The world’s largest secular egg?

***

Some sixty years after the Mentone Egg was constructed, someone from Mentone was listening to National Public Radio as a woman namd Mohja Kahf, a teacher of comparative literature in Arkansas, read a passage from her recently published novel, The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf. The listener’s ears perked up at the mention of “a twelve-foot high concrete egg” and then “Mentone.” Yes, the egg had achieved a teensy-weensy mention in contemporary fiction, and now that mention sat on bookshelves in libraries all across the country.

Overcome by curiosity, I picked up the novel from the library and read it through. Though not gripping it was interesting; detailing -- and as if from the author’s own experiences, fiction imitating life -- the difficulties of practicing the customs of the Muslim religion in a country that is predominately Christian, and adjusting to the strange customs of their adopted country. The reference to Mentone, on page 103, is fleeting. Some Muslims, including the narrator named Khadra, are travelling from Indianapolis for outreach to the Muslim community in Mishawaka. They missed turning north at Road 19 in Mentone (and would have been better off anyway to have taken an entirely different route) and find themselves, at prayer-time, pulled over next to a concrete egg. They spread their prayer rugs and turn their faces to Mecca. "Don't worry about people looking at us," Khadra's father said. "Focus on the patch of earth in front of you.

“My, how the ghost of Miss Aughinbaugh must have shivered to witness across the street a gaggle of young Muslim girls bowing toward Mecca in front of the egg to pray,” the NPR listener from Mentone remarked. He was referring to Miss June Aughinbaugh, our sixth-grade teacher, a fervent Methodist, now long dead, who in her Mentone days lived across the street from the egg.

And, fairly assuming that the novel is based on actual events, anyone who, at the particular time of the Mentone Egg event, happened to be driving past must have done a double-take, followed by a triple-take, and then turned around up the road to drive past again to assure themselves that they had seen what they thought they had seen.

And I wonder: Has the Winlock egg, the Vegreville egg, or the Alcochete egg found a place in contemporary fiction? I doubt it. I hope not. If my Mentone’s egg is not the biggest one in the world, then I at least want it to be the only contender that is mentioned in a novel.

***

At some point after 9/11, the Department of Homeland Security compiled something called the National Asset Database -- ostensibly a list of possible terrorist targets -- and, when all was almost said and done, it was revealed that Indiana had 8,591 potential targets, while New York, for instance, had only 5,687. Say again? Yes, in our bureaucratic and money-grubbing insanity, in an instance where hundreds of millions of dollars in grants would be passed out to protect potential terrorist targets, Indiana had something like a third more heritage-sacred and economic-critical sites than the entire state of New York.

New York is the home of the Statue of Liberty, of Wall Street, of Lincoln Tunnel, of numerous heavily-travelled and legendary bridges, of the Baseball Hall of Fame, on and on ... while Indiana is home to ... well, what? ... the speedway at Indianapolis? The home of James Whitcomb Riley? A boyhood home of Lincoln? Not the boyhood home but one of the boyhood homes. Would terrorists really have their eye on such?

Among the potential targets listed by Indiana authorities was a business called Amish Popcorn Factory near Berne. The owner, Brian Lehman, whose facgtory employed but five people, said to an Indianapolis Star reporter, "I don't have a clue why we're on the list. We're on a gravel road, not even blacktop. We're nowhere."

The state of Washington listed 65 national monuments and icons. Washington, D.C., where you can hardly turn your head without becoming a sight-see-er, petitioned that only 37 be put on the register of potential targest..

Otherwise, nationally, the list included a flea market, a petting zoo, several Wal-Marts, and a tackle shop. There were 700 mortuaries on the list, promptiing a Seattle Times columnist named Danny Westneat to put his tongue in his cheek and write, “Terrorists know no limits if they’re planning attacks on our dead people.” But no state had a greater number of strategically important sites than Indiana. A reporter for The New York Times, Eric Lipton, said, “A child might have written” the list.

“We don’t find it embarrassing, said the Department of Homeland Security’s deputy press secretary, Jarrod Agen. “The list is a valuable tool.”

Those Hoosiers have their treasures, and some of those Hoosiers know how to angle for funds from the government. (Or should I say “we” Hoosiers? If you are Indiana-born, you are a Hoosier. Nevermind that no-one knows why a Hoosier is called a Hoosier, but I am a Hoosier.)

The moment I heard about this National Database, and the astounding number of Indiana places on it, my main curiosity was whether the Mentone Egg had been designated as a potential target of terrorism. Was the Town Board on the ball, reaching out for some federal bucks to beef up security, or did they drop the ball?

***

Shortly after having read several news articles about the National Database I was chatting on the phone with my nephew Mike and happened to bring up the ridiculousness of bureaucracy, the hopelessness of it having any common sense, and I pointed to the example of Indiana having so many sites on the National Database of potential terrorist targets.

"What about the Arabs who tried to blow up Mentone?" Mike said. Mike’s a funny guy, and he was kidding. But behind his kidding there lay a sad story.

***

While I was growing up in Mentone there were three grocery stores. On the south side of Main Street was an IGA, but it went out of business in the mid-fifties when the owner, a newcomer to town, a Mr. Hoover, over-extended himself by, shortly after buying the IGA, opening a recreation parlor geared toward the town’s teen-agers. None of us had much money to spend on ping-pong and pool and soft drinks and pinball machines, but for volunteering to do some work in getting the place ready -- painting, lugging soda-parlor tables and chairs here and there -- my clique was rewarded with a good many games of free ping-pong before the official opening, and that official opening never actually occured because finances fell apart very quickly for Mr. Hoover. It could be said that the recreation parlor closed before it opened, closed even before the pool table, ordered from a tall handsome salesman from Indianapolis, had arrived.

Across Main Street from the IGA was Lemler’s Market; owned and operated by Fred and Lois Lemler, a well regarded couple, and my classmate Glen Davis reminded me recently that Fred Lemler was the best whistler he’s ever heard. Lemler’s market held on to enough business to keep going well into the eighties.

And then there was Frank & Jerry’s, on Road 19, a couple blocks south of the intersection of 19 with Road 25; it is fondly remembered by me mostly for the melt-in-your-mouth total deliciousness of the glazed doughnuts that were delivered once a week from some bakery in Fort Wayne, and which quickly sold out. There was nothing so absolutely perfect. I’ve since had glazed doughnuts in hundreds of places in hundreds of towns searching for such perfection, but nothing has come close.

When Frank and Jerry Smith, having outlasted the other grocery stores, and having Mentone’s grocery business to themselves, were ready to retire, they put their market up for lease/purchase.

Two Arabs arrived in town; papers were signed.

It seems almost needless to say that the Arabs took over what was already a dwindled market. And I wonder if many residents of Mentone would have been comfortable with these strangers in their midst; the two Arabs might have been the first not-exactly-white residents among the seven hundred-and-some residents of Mentone.

Further, Warsaw had come up with a supermarket in the late fifties, and then another, and then another, and most Mentoners had long since taken on the habit of driving the twelve miles to Warsaw for their groceries; prices were lower, variety was greater, and supermarkets, with their rolling baskets that you could push up and down the wide aisles, were a fetchingly new-fangled idea.

There was, in the middle of a June night in 2003, a tremendous explosion at Frank & Jerry's. The building was blown to smithereens. Sadly, one of the Arabs, Ismail Musleh, aged 35, was killed immediately; the other, Ismail's nephew Atta, only 19, was horribly burned but lingered on, suffering for two weeks in a hospital in Fort Wayne before he also died.

It was a time of suspicion and paranoia. Rumors flew. The word terrorist was hardly uttered without the designated Arab or Muslim preceding it. Never mind that there were plenty of terrorists who were neither ... Eric Rudolph, who bombed a club frequented by gay women in Atlanta, and an abortion clinic, and an Olympic site ... Tim McVeigh, who killed 168 people by detonating a truck-bomb in Oklahoma City (and remember how, within thirty minutes of that event, there was a BOLO bulletin for an “Arab-looking” suspect) ... Ted Kaczynski, who used the U.S. Postal Service to deliver some 16 bombs, killing three people and injuring another twenty-three. They were somehow different. They were evil guys, but at least they weren’t foreigners who addressed prayers to a different god than the one to whom most Americans prayed.

Mentone’s status on the map grew larger, at least in the imaginations of some locals who were anxious to believe that there may well be some sort of connection between their middle-of-nowhere and Osama bin Laden. Probably not a lot of doubt: the Arabs had been manufacturing bombs in the apartment above the store where they lived.

After weeks of investigation it was determined that Mr. Musleh and Mr. Atta, with hopes of collecting insurance on the contents of the building, and becoming untethered from their lease, had most likely been intent on fleeing with their lives what would be a building in flames but not exploding. Inexpertise, or a terrible accident, led to tragedy.

The state Arson Unit, in a statement, said that whatever chemical accelerant the Arabs had used had, when mixed with the water used to fight the fire, drained into the nearby creek and killed twelve hundred fish. (This would be the still-beloved Yellow Creek of my childhood, not a foot of whose bank I had not sat on and stared contemplatively at the flowing water, marveling that just 10 or 20 feet to the left or to the right, the character of the bank and the bed of the stream and the flow of the water would be vastly different, depending on the sun and the shade, depending on the winter and the summer, depending on a fallen tree or on boys and girls who had attempted to dam the water at a point in order to create a swimming hole, and I wondered where all that water was coming from and I wondered where it was flowing to, and I wondered when that place it was flowing to would finally have its fill.)

As for the dead Arabs, no autopsies were performed. The country coroner was quoted as saying that he didn't want to "waste taxpayers' resources."

***

Okay, this essay has meandered from here to there and I don’t quite know how to get it back on any sort of track.

I was talking about eggs.

And I had a thought that, well, if Mentone can’t be famous for having the largest egg in the world, it can maybe be famous for being the birthplace of Lawrence Bell. Growing up, it was often remarked, and it was taken to be true, that he had invented the heliocopter. Imagine! A little boy from Mentone growing up and inventing the helicopter.

Unfortunately, Lawrence Bell did not invent the helicopter. He founded Bell Aircraft in Buffalo, New York, and the company achieved many great developments in aircraft, including America’s first jet-powered plane, as well as the Bell X-1, the first aircraft to break the sound barrier in level flight.

Bell Aircraft began developing helicopters in 1941, but it was a man named Igor Sikorsky who is considered to be the inventor of the first helicopter, though others before him, including Leonardo da Vinci, had come up with the idea of rotary flight, and others had built helicopters that did not function well -- one flew a distance of one kilometer in 1924; still, it was Sikorsky who came up with the first successful helicopter.

Mr. Bell, who died in 1956, left $20,000 in his will to the town of Mentone to build a library; I have sometimes used and always admired the library which Mr. Bell’s money built.

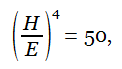

There was another aspect of Mr. Bell’s having been born in Mentone. In my day, the Senior class, using money raised through various projects through the years, such as selling candy bars and sodas at ballgames, made a trip to New York City and Washington, D.C. (The passenger train, which all year long zoomed through town, actually stopped at Mentone to pick us up one day a year.) At some point a stop at Buffalo, New York, was added, and the students were given a tour of Bell Aircraft. On my Senior trip, we not-quite-thirty classmates put out name in a hat. Some names were drawn and those who belonged to those names were taken up for a helicopter ride. In the picture below, classmate Tom Hoover and I are buckled in for a ride. It was exciting. I remember writing in a postcard to my family that I had a big surprise which I would have to wait to tell them about when I got home.

I had won a ride in a helicopter! Unbelieveable!

I once took the photo into a CVS pharmacy to have a copy made; they refused to do so because on the back is stamped:

Bell Aircraft Corporation

Post Office Box One

Buffalo 5, New York

Photographic Department

***

Had I got this post written by July 22, as I had intended -- so that it could be like a birthday card to my nephew Mike -- I wouldn’t have been able to report that Tom Hoover “passed away quietly at his home” on August 4 in Chesterfield, Missouri. I don’t quite know why I mention this, except that it seems relevant to the picture above, and since this essay has meandered all over hell’s creation, why not let it, at the end, meander to a lament that another of my classmates has “passed away”?

***

Big eggs ... a novel ... stupid bureaucracy ... grocery stores ... terrorism ... helicopters ... death.

No wonder it has taken me so long to get this written.